By Trudy Suggs

Read the 1997 article or the 2007 article. Scroll down to see my thoughts about this year’s results.

A survey sent to 40 schools in the fall of 1997, revealed, to many people’s surprise, that no deaf school had a majority of employees who were deaf. Out of the 21 schools that responded, the highest percentage was 46% (at the Model Secondary School for the Deaf and California School for the Deaf in Fremont) — not even 50%. Following a close second was Maryland School for the Deaf, at 41%.

Ten years later, in the fall of 2007, this same questionnaire was distributed to 57 schools, with 46 responding. The highest percentage was 55% for Maryland School for the Deaf, with Indiana and Washington at 50%. Even so, the numbers remained the same or even lower at many other schools.

In the fall of 2017, this questionnaire was once again distributed, with 27 schools responding. In the past, only residential schools were contacted, but for this year, charter schools were also contacted.

The deaf staff percentages were higher this time around, with the highest percentage going to the Clerc Center (Kendall Demonstration Elementary School and Model Secondary School for the Deaf) at 78% of employees being deaf, and two charter schools following at 69% and 66%. Next were Maryland at 65%, Indiana at 64%, and California (Fremont) at 63%. There has also been an increase in deaf superintendents, with the number growing to 24 in 2017, according to a database compiled by Joey Baer, who is Deaf and works at the California School for the Deaf in Fremont.

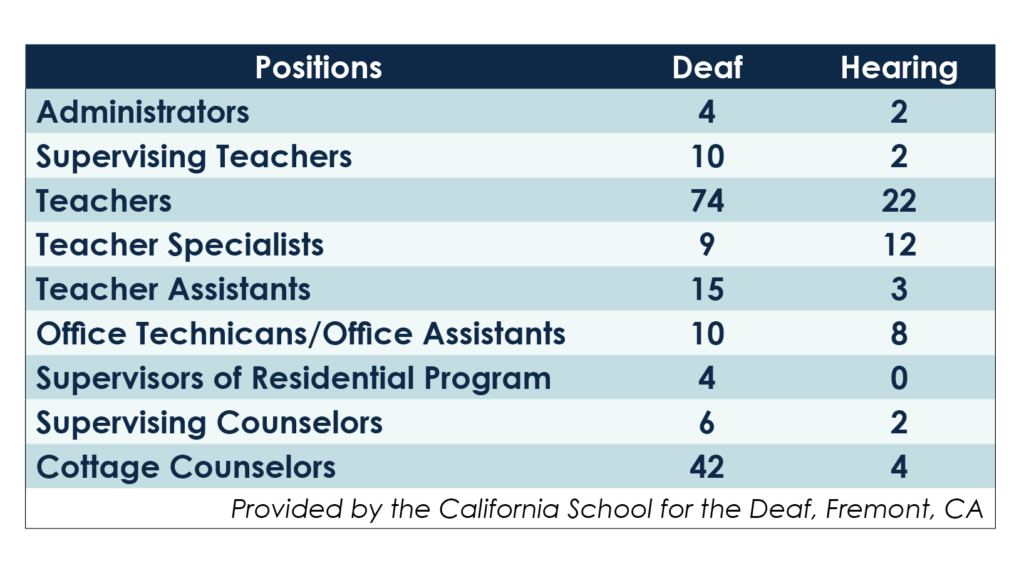

However, it is crucial to recognize that the statistics include all levels of employment — from entry-level to administration. If each set of data were isolated by administration only, or teachers only, the numbers would likely paint a different picture. Just take a look at California School for the Deaf in Fremont’s breakdown of its numbers:

Peter Bailey

Peter Bailey, Head of the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf in Philadelphia and Deaf himself, attributes the increase in the hiring of deaf employees to “the timing of modern changes. People are more aware of what deaf students need, such as full access and seeing adults just like them. In the past, we had limited resources and options, but now they’re more broad.”

Teaching Profession No Longer Top Choice

The low numbers of deaf employees at many deaf schools may be credited to a number of reasons, such as location, student population, and credentials, according to Bailey. “Schools in rural areas may have a harder time recruiting deaf employees, while schools in large cities generally have more choice in application pools. This is true for any job, really.”

Dr. Bradley Porché

Dr. Bradley Porché, Superintendent at the New York School for the Deaf in White Plains (more commonly known as Fanwood), agrees. “Schools with larger student bodies typically have more applicants than those with smaller bodies, but at the same time, we’re not seeing the same pipeline churning out teachers as we have historically.”

Porché,who has been at Fanwood for nine months, cites increased accessibility and media visibility as possible reasons. “Social media may be a factor, in that younger generations are seeing people like Nyle DiMarco and other deaf people rise to incredible success,” he explains. “There are so many successful deaf people in a variety of fields, and as the media has reported, the teaching field is severely underrated, underpaid, and unappreciated. Teaching is an incredible profession, one that should be celebrated and respected. Yet many deaf people, just like their hearing counterparts, see the drawbacks to teaching and choose to go into other fields because they don’t want all the stress that comes with teaching.”

This echoes an observation by Texas School for the Deaf Superintendent Claire Bugen, who said in the 2007 article, “Clearly, deaf people have many more career choices today than in the past, and with changing technology I suspect that will only continue to be a factor – that’s a good thing. Salaries in education, on the other hand, have not kept pace with the private sector and many young people both want and need to be paid better than most educators are paid. Now with the requirements of highly qualified teaching under various laws, our already shrinking pool of qualified deaf and hearing candidates is compromised even further, which will likely cause more challenges in the years ahead.”

In a September 2016 article in The Washington Post, a new study revealed that there was a nationwide shortage of teachers. The article reported, “Although nearly every state has reported teacher shortages to the U.S. Department of Education, the problem is much more pronounced in some states than others. But across the country, the shortages are disproportionately felt in special education, math and science, and in bilingual and English-language education.”

Dean of Graduate and Professional Studies at McDaniel College J. Michael Tyler wrote in an April 4th Facebook post that the McDaniel deaf education graduate program was facing an uncertain future.

This shortage has affected deaf education training programs as well. On April 4, the dean of graduate and professional studies at McDaniel College, J. Michael Tyler wrote in an announcement shared on Facebook, “Due to ongoing enrollment issues in Deaf Education [sic], a decision has been made that we will be unable to start a new class in the fall of 2018. We will start a new class this summer, and all introductory courses will be offered. Graduate and Professional Studies faculty will work in the next 90 days to determine if there is a viable path forward for this program.” McDaniel, formerly Western Maryland College, has been a popular graduate program for those wanting to become teachers in deaf education.

Tyler further wrote, “Enrollment in Deaf Education [sic] has been in decline for a number of years. While low enrollments have created serious revenue issues, ultimately the College’s ability to deliver a strong, vibrant program that meets the needs of students pushed us to this point.”

Credentials

Credentials and certifications continue to be a challenge, as in 1997 and 2007. Testing standards have become so difficult that many choose to become paraprofessionals or teachers in fields that don’t require testing. In an attempt to address this, Minnesota passed a state law permitting deaf teachers to request exemption from the reading and writing portions of the examination process in order to gain licensure. As outlined on the Minnesota Professional Educator Licensing and Standards Board, “…an applicant who is deaf must complete the skills examination in mathematics adopted by the Professional Educator Licensing and Standards Board. The reading and writing skills requirements can be completed by either passing the examinations adopted by the Professional Educator Licensing and Standards Board or by an evaluation completed by board approved colleges and universities of demonstrated proficiency in the expressive and receptive use of alternative communication systems, including sign language and finger spelling as measured by the Sign Communications Proficiency Inventory (SCPI).

Bailey came to PSD after the school experienced numerous challenging years in which it had several heads of the school, community protests over board decisions, and strained community relations. In under two years, Bailey has managed to repair many strained relationships, and increase the number of applicants by offering incentives for employees to pursue teaching credentials through reimbursed tuition, tutoring, and other options. “Whatever I can do to help encourage the growth of teachers who our students can identify with, the better,” he says.

Meanwhile, Porché points out that he’d like to see teachers be hired based on their work experience and knowledge, rather than testing. “I’ll always ask to see a teacher’s portfolio, because that tells me far more than what a teacher’s test scores do,” he says. “I always tell state legislature that teaching is an art and a skill that is acquired, not something you can just be tested on.”

The Lack of Diversity Among Employees

Another challenge is the lack of diversity among employees at deaf schools. Bailey says that at PSD, “We have about 74% of students of color, yet only 46% staff of color. The challenge for me then becomes: do I hire people who are deaf, or people who are of color? Ideally, we should hire deaf people of color, which I want to do. But we can only make do with what we have in our application pool, and try to reach out to diverse communities as much as possible.”

And this is a step Bailey takes seriously. He attended the National Black Deaf Advocates conference in Baltimore last year, and recalls, “I was surprised to see that only two superintendents were in attendance, and we were both deaf.” The other was Donald Galloway, Superintendent of the Lexington School for the Deaf in New York City. “Why were we the only ones there? How can we ensure that our schools serve underserved and oppressed populations if we don’t reach out? And how can we hire more people of color if we don’t pursue them?” Bailey asks.

Language Deprivation and Outreach Efforts

Yet another obstacle is that many deaf schools have become a last resort, rather than a first resort. Deaf students often come to deaf schools later in their educational years, severely delayed in language, socialization, and world knowledge. As a result, schools invest more time trying to catch these students up before they graduate.

Bailey notes that there are over a thousand students who are deaf or hard of hearing in the Philadelphia area, yet only 200 attend PSD. “Where are they? How do we bring them in earlier in their education, rather than later in their education after they’ve experienced language deprivation and delay, not to mention a lack of socialization or opportunities?”

This is a problem that Porché wrestles with. “A lot of time students are language deprived because of the lack of access to language at an early age. This places a stress on schools to try to address this language deficiency and to ensure that students receive quality education.” He notes that Fanwood shares with the community and parents that “deaf and hard of hearing children should be exposed to American Sign Language at an early age as a safety net regardless of hearing level or communication choices. We need to work with everyone to reach a common dialogue on how to best support deaf children.”

Bailey is also working hard to ensure that PSD becomes attractive not only to families of deaf and hard of hearing children, but also to potential employees and community members. As part of outreach efforts, Bailey has developed a solid relationship with neighboring communities, legislators, and even the Chamber of Commerce.

“By becoming more visible, it’s more possible we can reach out to more families,” he says. He also releases a monthly vlog on the PSD website, which has helped strengthen relations between stakeholders and the school board. “It’s my hope that with increased visibility, we’ll have increased student enrollment, which will naturally lead to increased employment opportunities and a greater applicant pool.”

Rising to the Challenges

Porché believes there are many solutions to the long list of challenges facing deaf schools. “One potential solution is to invest more in early childhood education via an outreach or intervention program that would guarantee success across the spectrum,” he says. “We also need to ensure that key people who are deaf or hard of hearing are more involved in outreach so that parents are exposed to more than just a language. They need to see that there are successful deaf people in every area possible.”

Porché further suggests working at the legislative level to ensure that mandates for academic standards and language access are enacted, such as those supported by the Conference of Educational Administrators of Schools and Programs for the Deaf (CEASD): the Child First, Alice Cogswell, and Macy Sullivan Acts.

Porché also points to the Language Equality and Acquisition for Deaf Kids (LEAD-K), a nonprofit organization that is rapidly gaining momentum. LEAD-K states on its website that it works to “end language deprivation through information to families about language milestones and assessments that measure language milestone achievements, and data collection that holds our current education system accountable.” LEAD-K also works to ensure that all deaf and hard of hearing children, regardless of communication choice, are kindergarten-ready.

Indeed, more and more schools have turned to early hearing detection and intervention programs, ensuring that their schools are included in informational packets given to parents of newborn babies identified as deaf. For example, in Maryland, all parents are automatically referred to the Maryland School for the Deaf when their babies are identified as deaf. More schools are also offering programs designed to accommodate students with cochlear implants.

Despite all the challenges, it is certainly motivating to note that there are now 23* superintendents of deaf schools or charter schools who are deaf. Porché, who is Deaf and was raised in a mainstreamed setting in Louisiana, says, “I grew up not having [access to] all the features a deaf school provides, such as full communication access, athletics, deaf role models, and much more. I’m now in a position to make sure every deaf or hard of hearing child has these opportunities. My leadership style is a reflection of my upbringing in a flawed deaf education system, and I want to make sure students today experience things I never did, and that I can give them what I didn’t have.”

Special thanks go to Joey Baer for his assistance with superintendent data.

*At the time of this survey last fall, there were 24 deaf superintendents. However, in March 2018, according to The Daily Moth, Nancylynn Ward was relieved of her duties as the Tennessee School for the Deaf superintendent after eight months on the job.

In the time since the 1997 article, I’ve had four kids, all Deaf (all born after the 2007 article). My oldest is now a fourth grader, and we’ve relocated from one state to another. Being the Deaf parent to Deaf children has added to how I experience the deaf education system. I’m also married to a Deaf teacher who has worked at four deaf schools, including a charter school, for 23 years.

An interesting result of this survey was that the first schools to respond were all Deaf. Yet so many schools were reluctant to share data, which isn’t anything new — they’ve been reluctant in the past, too, as I shared in the 2007 article. I suspect this reluctance is because of a few things:

- They didn’t want to admit that their numbers were nowhere near where they should be.

- In today’s social media age, they were uncomfortable with how this information might backfire and be used against them.

- They didn’t want to face that they were possibly perpetuating audism.

I didn’t bother chasing them after the second request for data. Schools should be forthcoming with their data, whether it’s about deaf people, people of color, communication philosophies, or anything else affecting schools — after all, this information is generally public information.

As I read through the data, I was struck by one thing: how many hearing employees continue to work at deaf schools. Mind you, I’m not talking about those who have direct relationships with the Deaf community, such as those with Deaf family members. Rather, I’m talking about those who have no direct relation to the Deaf community, and just work there by chance.

At the previous school my children attended and my husband worked at, there was a good number of Deaf employees. Yet the school was strongly hearing-centric. Many of the hearing employees had worked there for at least 10 years, even 20 or 30 years. Many still couldn’t sign fluently, of course. I often wondered why they stayed for so long, when so many Deaf people were struggling to get jobs at the school. Job security, perhaps. That school was in a very small town, where jobs weren’t as readily available as in a bigger town.

Many hearing employees obviously have the heart and soul for working with Deaf people — but are their intentions misplaced? Are they taking jobs away from Deaf people who already face a 70% underemployment/unemployment rate? I think so, yes; In most cases, they can find employment elsewhere more easily than their Deaf counterparts. They are also taking away opportunities for Deaf people to build the village our deaf children need.

The difference between a school that has a majority of Deaf employees and a school that has a majority of hearing employees is day and night. I should know; I’ve experienced both environments. My children are products of deaf schools, and I have seen firsthand the major difference a Deaf-centric school, staffed by mostly Deaf people, has made. Don’t get me wrong; hearing people absolutely should work at Deaf schools, but not as a majority. The hearing people who do work at my children’s school almost all have direct connections to the Deaf community, which is reassuring.

I’ve also seen how many schools have seen their enrollment numbers dwindle. We left the previous school for many reasons, one being that one of my children had no peers in his grade. He was four and performing well above his grade level, yet he was placed in a preschool classroom with two-year-olds because the school simply didn’t have anywhere else to put him. The school wasn’t willing to accommodate his academic needs, so we saw no option but to move.

At my children’s current school, each child has 15 students, give or take, in each grade, with plenty of peers, resources, and role models. With this critical mass comes an amazing array of opportunities in academics, athletics, and socialization. I’ve seen my children blossom at their school in ways they wouldn’t have at the old school simply because of this much-needed critical mass.

Yet I feel guilty for having left the old school. That school lost as many as 20 students within a three-year period to other, bigger schools. If the school dwindles in enrollment, that means job opportunities for Deaf people dwindle, students at that school are provided with fewer Deaf role models, and so on — a domino effect.

This is the classic “who came first” question: the chicken or the egg? Did we need to stay to help maintain the school’s enrollment numbers, or did we need to go where there was already a critical mass? We struggled with this decision, and chose the latter. The school we left has seen its enrollment dwindle from 130 to about 100 in just a few years. If that school should ever close, is it partly our fault? Or is it the school’s fault for not meeting our children’s needs? Which comes first?

There, of course, are other obstacles to employability among deaf people at deaf schools: teaching credentials, wanting to work in different fields, and job availability. Still, I think the numbers could certainly be as high as they are at the top schools listed in this survey. So why don’t we work toward that? After all, the numbers have steadily increased at many schools over the past 20 years — which I see as wonderful news.

What will the numbers be like in 2027? Your guess is as good as mine…that year, I’ll have three children still in high school. So I’ll see you then.

This article cannot be copied, reproduced, or redistributed without the written consent of the author.