Two incidents took place recently that made me think about the inherent, subconscious biases that we all carry and how they spill over into our interactions with others. The first incident was when I took my two-year-old daughter in for allergy testing. We went to a different clinic from the one we usually go to, so I wasn’t sure who the interpreter would be. The interpreter arrived a bit out of breath because he was late, but he was pleasant enough.

My daughter, as she usually does with anyone who even as much looks at her, started chatting away with the interpreter in American Sign Language (ASL). Keep in mind that the appointment was for my daughter, and so the interpreter was primarily there to facilitate communication for her, although he obviously was there for me also. I found it worthy of note that he never once asked what our communication preferences were.

Halfway through the appointment, as we were waiting for the nurse to return, the interpreter and I began chatting politely. He said, referring to my daughter, “I’m impressed by her language. Normally, with kids that age, I have difficulty understanding their ASL, but she’s so clear and easy to understand.” [Read more…]

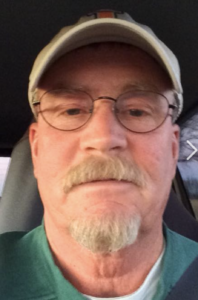

David Reynolds, 63, became an educator and worked for years at the Indiana School for the Deaf before moving west to Fremont, Calif. He has three sons, and has an acting career, most notably as Dr. Wonder on

David Reynolds, 63, became an educator and worked for years at the Indiana School for the Deaf before moving west to Fremont, Calif. He has three sons, and has an acting career, most notably as Dr. Wonder on

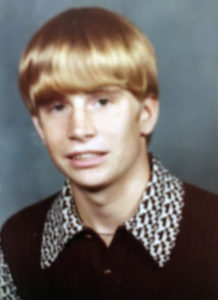

When I think of Chuck, I remember how he had the chubbiest fingers and how I took pleasure in watching them create masterfully crafted words and art. I think of how we squabbled often, but always quickly soothing the other. I think of how I scolded him for being so tactless — he once said, when I showed him a picture right after the birth of my second child, “Oh my gosh, you look fat!” I think about how he got annoyed with me for being bossy, especially when I lectured him about his weight; our annoyances certainly went both ways. I think about how he had such a passionate spirit. I think about how shockingly salt-and-pepper his hair was and how his beard became the same. I think about how we always laughed at the littlest things.

When I think of Chuck, I remember how he had the chubbiest fingers and how I took pleasure in watching them create masterfully crafted words and art. I think of how we squabbled often, but always quickly soothing the other. I think of how I scolded him for being so tactless — he once said, when I showed him a picture right after the birth of my second child, “Oh my gosh, you look fat!” I think about how he got annoyed with me for being bossy, especially when I lectured him about his weight; our annoyances certainly went both ways. I think about how he had such a passionate spirit. I think about how shockingly salt-and-pepper his hair was and how his beard became the same. I think about how we always laughed at the littlest things.