As I entered the small exhibition area, I jumped in fright. To my right, there was a person blankly staring at me. Don Baer laughed as I did a double take; I realized (slowly) that it was actually a wax figure of William “Dummy” Hoy that Don had created. The first thing I thought after I looked at the wax figure, “Wow, Hoy was really short.” Even though I had known Hoy was only 5’4”, I was amazed at how much taller I was than him. What was even more remarkable was how I felt as if I could reach out and start signing to Hoy right there and then. That was, and is, the best aspect of Don’s work in creating realistic wax figures: he helped bring Deaf history alive.

As I entered the small exhibition area, I jumped in fright. To my right, there was a person blankly staring at me. Don Baer laughed as I did a double take; I realized (slowly) that it was actually a wax figure of William “Dummy” Hoy that Don had created. The first thing I thought after I looked at the wax figure, “Wow, Hoy was really short.” Even though I had known Hoy was only 5’4”, I was amazed at how much taller I was than him. What was even more remarkable was how I felt as if I could reach out and start signing to Hoy right there and then. That was, and is, the best aspect of Don’s work in creating realistic wax figures: he helped bring Deaf history alive.

When I was Silent News editor in chief, the first public event I attended was the 2000 Deaf Expo in Long Beach, Calif. Everyone there told me I had to see Don’s wax exhibition at the exposition. As I introduced myself to Don, who was also small in stature, he lit up and named a few mutual friends. His wonderful passion set the tone for the tour, and we chatted endlessly as he guided me through the packed exhibition area. I gawked at how realistic the wax figures were, and marveled at Hoy, Juliette Gordon Low, Thomas Gallaudet, Alice Cogswell, and Laurent Clerc. Seeing the figures made my cherished heritage come alive for me. It was obvious from looking at Don’s face, as people continuously marveled at the authentic-looking figures, that their awe was the best part of his hard work.

In a June 2001 Silent News article by Glenn Lockhart, Baer said renowned sculptor Douglas Tilden heavily influenced his work. The article also reported that each sculpture’s process averaged three months of work and over $1,000 on average:

A clay sculpture that serves as a frame for the head is done following dimensions gleaned from the photographs, then a plaster mold is made from it. After the mold has set, it is then emptied of clay and filled with hot wax. After adding glass eyes and hair, some refinement sculpting brings sharp definition to the facial features and a coat of oil glazes the wax, giving it that realistic sheen. A trip to thrift stores to costume the waxen beings is the final touch.

When I learned last week that Don had passed away on Dec. 10 from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis — also known as Lou Gehring’s disease — I was, of course, saddened. I have no idea if he would have remembered our visit, but the work he took on left a lasting impact on many people, including me. I hope his work continues to bring history alive for future generations.

Don’s work can be viewed at www.deafwax.com (link is no longer active).

Copyrighted material. This article can not be copied, reproduced, or redistributed without the express written consent of the author.

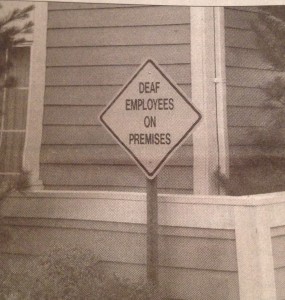

This made me think about when I lived in southern New Jersey. I was on a shuttle back from the airport, and we stopped at a hotel to let a passenger off. I noticed a sign in front that stunned me: DEAF EMPLOYEES ON PREMISES.

This made me think about when I lived in southern New Jersey. I was on a shuttle back from the airport, and we stopped at a hotel to let a passenger off. I noticed a sign in front that stunned me: DEAF EMPLOYEES ON PREMISES.