This article originally appeared at i711.com.

This article originally appeared at i711.com.

An Alton Telegraph (Illinois) article reads in part:

Springfield, Ill. (AP) – About 100 deaf citizens carried placards and used their hands to talk at a silent rally in the State Capitol aimed at supporting legislation that would affect the deaf.

The demonstrators came from all over the state to…testify before an Illinois House committee and meet with Gov. James R. Thompson.

The Human Resources committee then voted 18 to 1 in favor of a proposal to provide communication devices for the deaf in at least one emergency facility in communities with more than 10,000 residents.

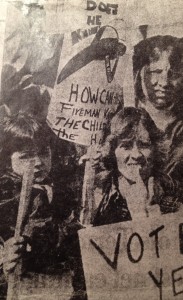

I don’t quite remember my first rally, but I do remember Mom sitting me down and talking with me about how we could make our home safer in the event of a fire or other emergencies. Back then, we were too poor to own a TTY, so we had to rely on alternate methods. The next day, a group of deaf people gathered to make signs and flyers; I colored the fireman’s hat on my sign a bright red. Then we went to the state capitol. I remember meeting with Governor Thompson in his office and being in awe of how tall and friendly he was. I was only three years old; Mom was 25. The rally and governor’s meeting were crucial lessons for me.

Today, nearly 30 years later, I continue to believe in the value of children participating in peaceful rallies and demonstrations. As a result of that early exposure – and many other rallies or demonstrations – I developed a lifelong interest in advocacy. I stay active with both state-level and national-level associations serving deaf people not because it’s a “cool” thing to do, but because it’s the only way we can ensure our rights.

There was recently some discussion recently among bloggers and vloggers about whether children should be involved in demonstrations or protests. This dialogue emerged from an incident during the A.G. Bell conference in Virginia last July. A group of people, including an A.G. Bell member, passed out flyers at the conference site promoting the teaching of sign language to deaf babies. The Marriott hotel manager, Jenny Botero, was captured on video trying to take flyers away from one of the people. Botero also grabbed paper from a frightened deaf eight-year-old daughter of a deaf woman, though this wasn’t captured on video. The girl’s mother was understandably furious. One blogger questioned the mother’s judgment and integrity in having her daughter participate, yet never once questioned Botero’s integrity. Regardless of the circumstances, no adult should ever try to intimidate an eight-year-old – or any child – into doing anything to further a cause.

When I read the blogger’s article and people’s comments agreeing that children shouldn’t be involved in events like this, I was saddened. The deaf community is now beginning to associate the word “protest” – or other forms of activism – as aggressive, dangerous and harmful. And this association has serious consequences.

I certainly don’t support dangerous tactics, regardless of results. Not all activism include dramatic events like what sometimes happened during the Gallaudet protests or even the civil rights movement of the 1960s. I should, however, point out that many of the children who were involved with the Deaf President Now protest are now adults, even parents, who have become even more cognizant of the importance of advocating for issues important to them. Many of them have become outstanding community leaders in individual ways. I was 13 when DPN happened, and the protest certainly left its mark on me. It didn’t teach me that we had to resort to violent methods. The protest taught me that deaf people like me were just like anyone else who deserved equal respect and access, and that we could play smart in order to get what we wanted, or rather, needed. It’s still that simple today.

So, to bring the kids or not? Again, it’s simple: the parent has the responsibility of gauging the safety level of each event, whether a rally, demonstration or a protest. The parent also has a responsibility in developing a safety plan should things go terribly wrong – whether at the hands of the protestors or the police or management. And the parent also has the right to decide if a child should be involved or not. Let’s be real: there’s a degree of risk in everything we do, from carrying signs at an event to riding a car (anyone want to compare the likelihood of dying in a car accident to being hurt during a demonstration?).

Besides, any responsible parent would do what my mother did: sit with the children, talk about the issues at hand in as neutral and factual a manner as possible, and then explain why the event is taking place. Then the parent could ask if the children want to be involved or not. Safety should always be a priority, but so should education and awareness.

Even though my first rally was three decades ago, I find myself advocating for the same issues we did back then, which was pre-Americans with Disabilities Act, pre-captioning, pre-Internet, and pre-everything: equality. And if it takes another 30 years of peaceful demonstrations and rallies to achieve equality, so be it. Our children should not face inequality at any time, so what better way to educate them than to include them?

Copyrighted material. This article can not be copied, reproduced, or redistributed without the express written consent of the author.