By Trudy Suggs (Click here for my thoughts on this story in ASL and English).

PART 2 (Read Part 1 here)

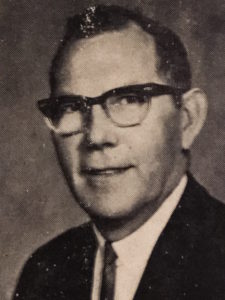

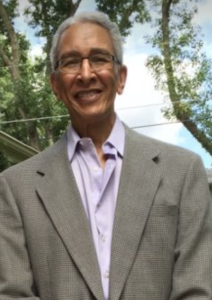

Zeke Beranek was the sole chaperone, along with the school bus driver, for 40 boys. Many credit him for his calm demeanor during the crisis.

Zeke Beranek: The Unsung Hero

Zeke Beranek was the sole chaperone of 40 boys — something that would never happen today. “Well, how I did it was I set up a buddy system. I had the older boys be responsible for the younger students,” Beranek explained. “The boys who went on this trip had been allowed to go based on their grades and good behavior. But I had more faith in the dorm parents, who were with them all the time, than their teachers, so I trusted who the dorm parents said should go on the trip. It worked out well for the most part.”

Only 37 at the time of the fire, Beranek looked older than his age, although he was rarely without his sense of humor or smile. A well-respected gentleman from Nebraska, he was popular among the students. As a Boy Scouts leader and school teacher, Beranek often took the boys camping and on trips. “The way I saw it was that whenever the boys achieved the Eagle Scout rank or did good things, this was good publicity for ISD,” Beranek explained. “It helped bring awareness to the school.”

And then the fire happened. “I can’t remember how I knew there was a fire, but I woke up and opened the door. There was smoke, and I began trying to do what I could,” Beranek said. “I wanted to wake as many boys up as I could, but it wasn’t possible.”

He continued, “I opened Freeman Harper’s room, and I saw him talking with a few scared younger kids near an open window. One of them started to jump, and Freeman told the kid, ‘Don’t jump! Don’t forget about me!’ That was his way of convincing the kid to not jump.”

The boys learned later that after being rescued Beranek had gone above and beyond in his role as chaperone. “Mayor Daley provided a police escort when he learned who I was and what group I was with, and I instructed [junior] Pedro Medina to be in charge of the boys,” Beranek remembered.

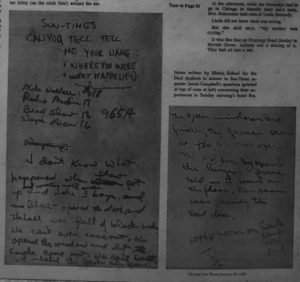

Written notes between ISD students and newspaper reporters.

He saw a group of reporters clamoring to interview the boys at the hotel, and was disgusted. He told the reporters, “Leave the boys alone, they’ve already been through enough.” When they didn’t cooperate, Beranek immediately notified hotel security. “Someone from the Hilton hotel did physically have to pull the reporters away.”

The church service the group was supposed to attend that morning had secured an interpreter. Beranek said, “The church didn’t know yet about the fire, and they actually held off starting the service for about 20 or 25 minutes, waiting for us.”

As soon as the church learned of the fire, the interpreter went to help Beranek as much as possible. “In fact, when I left Chicago, the interpreter said he’d keep visiting the kids still in the hospitals until they were all gone,” Beranek recalled.

The Smoke Clears

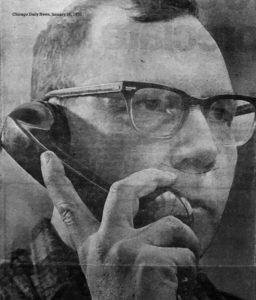

After all the chaos eventually settled somewhat, Beranek also had to make arrangements for that evening’s lodging and transportation. The boys clearly could not attend the Bulls game, so some boys had been picked up by their parents, and the remaining boys relocated to the Palmer Hotel, also owned by the Hilton family. Reynolds wondered if his parents, who lived just over an hour away, would come. He had no way of contacting them; although they were Deaf, they didn’t own a TTY.

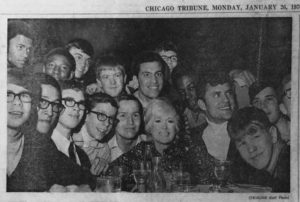

The ISD boys went to Connie Stevens’ performance the night after the fire. Reynolds is fourth from left in the front row; Albert Jones is second from left in the back. Robert Perry, who later drowned, is third from right in the back behind Connie Stevens.

Entertainer Connie Stevens was scheduled to perform at the Palmer Hotel that evening. When she learned of the tragedy, she invited the ISD boys to come to her performance. Saline remembered, “We were given free food on Mayor Daley’s tab. We were treated like royalty. We were also asked to fill out insurance forms to get reimbursed for our belongings and clothes.”

Yet most of the boys were too dazed and could not eat much. Reynolds’ throat hurt too much to eat, and he had lost his sense of taste. They tried to keep their spirits up despite the horrible tragedy. “She sang all evening, and when she spoke to the crowd, we were seated in the upper balcony and she made sure to look at us,” Reynolds said. “After her performance, she came to us and posed with us.”

That evening, the boys retired to their rooms. Five firemen, including a fire chief, stood guard by their doors overnight. Reynolds roomed with Jim Gurley, and as they got into bed, Gurley kept saying, “Look at the door. I see smoke. Do you?” Reynolds indeed could have sworn he saw smoke coming under the door, too. They decided to leave the light on and try to get some sleep. They didn’t get much, of course.

Monday Morning

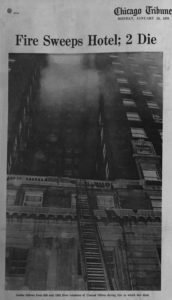

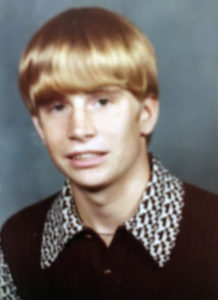

Beranek woke each of the boys up, telling them it was time to return to Jacksonville. They got early editions of the Chicago Sun Times and Chicago Tribune, and there it was for all of the world to see: two “deaf-mutes” had died. It was a punch in the guts for the boys. Although they already knew Zanger and Kennedy had died, they now felt a mixture of sadness and survivor’s guilt.

The group gathered in a conference room, and Beranek told the group, “As I woke each of you up, I noticed that more than three-fourths of you left your lights on overnight.” When Reynolds learned this, he let out a sigh of relief. He had thought he was going crazy with the need to leave his light on. They all had suffered a horrible trauma that was intensified by the lack of communication access. Worst of all, they had no psychological support. There were no counselors, no trauma advocates, and no family nearby. Although some parents had already picked up their boys, many of the boys’ families lived too far away (some as much as eight hours away) and others had no idea what had happened. They only had each other.

Reynolds later learned that his parents didn’t know about the fire until Sunday evening, when his hearing brother told them to look at the TV. The news reported on the fire, and his parents began to worry. They made his brother call the school, but there was no information yet. When they saw the newspaper on Monday and Reynolds’ name was listed among those hospitalized, they panicked, thinking he had been badly burned. They couldn’t sleep all night, trying to figure out what they should do.

As the boys climbed silently back on the yellow bus, Reynolds looked up at the overhead bins and realized that Kennedy’s pillow, streaked with mud, was still there. He sadly remembered how Kennedy had thrown the pillow at his friends, laughing, as they rode to Chicago.

Beranek stood up as the bus rode along, and talked to the boys in his SimCom style of what had transpired over the weekend. He shared that he knew some students were in their rooms, but he didn’t realize that several, including Zanger and Kennedy, had gone into the hallways. He didn’t know until later about Bright’s jump, which continues to be a legend in the Illinois Deaf community even today.

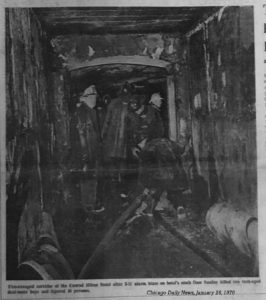

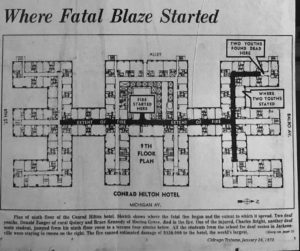

Saline and Reynolds both remembered how Beranek shared the rumor that Zanger and Kennedy had been found near each other by the elevators, but that this hadn’t been confirmed. (Newspaper articles reported Chicago Fire Commander Robert J. Quinn as saying that the two boys’ bodies were found outside a room on the north end of the corridor; Quinn added that had the boys stayed in their rooms, they likely would have survived.) Beranek also told of how he had to go to the morgue to identify the boys’ bodies, which were badly covered in soot. As Beranek spoke, every boy on that bus shed tears. The ride to Jacksonville was eerily quiet, with Kennedy’s pillow literally hanging over their heads.

The Aftermath

Reynolds remembers vividly how upon arrival, the school bus was swarmed by other ISD students, and the sense of dread he and the other boys felt. “We should’ve had trauma counselors on the ready for us, instead of kids wanting to know every detail about our experience,” Reynolds says. He saw many cars, mostly driven by hearing parents, waiting to pick up their boys. He walked to his dorm and as he put away his things, a houseparent notified him that his family had called.

Reynolds quickly went to pick up the phone and call his family. When his brother picked up, “It was at that moment that I realized I couldn’t speak. I had lost my voice, and could only speak a few words.” His brother asked, “Are you okay? Are you okay?” Crying, Reynolds responded that he was okay and that he loved them.

Meanwhile, Saline’s mother and niece drove down from Rio to see him that evening, and took him out for dinner at the local Hardee’s. They wrote back and forth, talking about what had happened.

The next morning, the survivors went to class on the second floor of the main building. Saline said, “So many people hugged me, and it was weird. It was really hard on me, knowing that Donald, who was my roommate at the hotel, and Bruce both had died. I wondered about them for a long time, and it took a while for that feeling to wear off.”

Soon after class began, Reynolds was thrilled to learn that his parents and brother were there to pick him up. As soon as he made his way to the first floor, his brother ran to him. Reynolds recalls bittersweetly, “I never had that hard of a hug from my own brother before that, and it was the best feeling.” He went home for a week.

Upon his return, Reynolds practiced with the school basketball team. On game day, on the court in uniform, he had one of many epiphanies. “I was warming up, and as I was dribbling, I looked around the gym. There were people in the bleachers, I was playing with my teammates, and I thought, I’m alive. I have another chance to play basketball. My view of the world changed at that moment, and I embraced my newfound maturity. I ran and did a lay-up, never forgetting the boys we lost in Chicago.”

Bright went home after seven days, where he had virtually been isolated from the world. After all, back in those days, TVs were inaccessible and no interpreters were provided. Newspapers reported that he would not return to school that year. After two weeks, though, Bright was going stir-crazy. He was the only deaf person in his family and town, and missed his friends. He begged his parents and ISD superintendent Dr. Kenneth Mangan — who wasn’t too fond of him, since he was somewhat of a troublemaker — to let him return. Bright’s doctor felt he wasn’t ready, either, but Bright lied and told Mangan that the doctor had given approval.

Mangan still refused. Dean of Students Lawrence Huot spoke on Bright’s behalf, and finally convinced Mangan to let Bright return. Mangan finally agreed to let Bright return. Bright walked using specially fitted crutches for about a month, but was overjoyed to be back. Reynolds and others were stunned to see Bright back so soon after his near-death experience. “We all thought Bright would be crippled for life, and even today, I am astounded he survived,” Reynolds said.

Bright was thrilled to be back, and wasted no time in healing. He went on to have a noteworthy athletic career both in the last years of high school and in adulthood, and graduated with his classmates in June 1972.

Charles Bright, shown here with his mother and their family lawyer, had to return to Chicago for a medical follow-up visit. (Courtesy of Charles Bright)

Bright also remembers how a lawyer representing the Hilton corporation showed up at his house and convinced his parents to sign a $10,000 agreement, although today he isn’t sure what the agreement stipulated. When Bright returned to Chicago for further medical care, his family lawyer accompanied him — and his mother wouldn’t leave Bright’s side during an overnight stay at the hospital; she was too afraid something would happen again.

For decades, Bright refused, and still refuses, to stay overnight at the hotel where the fire took place, even when softball or basketball tournaments were headquartered there. In 2014, Reynolds and Bright returned to the hotel, now named the Hilton Chicago. Although they had been back to that hotel for various events, this time was different: they were going to confront their memories and visit the ninth floor. Bright says, “I had a sense of trepidation, and it was difficult to see that floor again. So much of the hotel looked the same, yet so different.” Reynolds echoes this, which is why he wants to create a film based on this experience.

“It’s the little things that jump out at you,” Reynolds said. “I still have my room key from that night.” For Bright, one of the small details was that he had borrowed his good friend Ronald Sipek’s suit for the weekend, which then was destroyed in the fire.

Beranek, when asked how he recovered from the terrible events of that weekend, said, “It bothered me for so very long, yeah. It bothered me until that kid, what’s his name? Perry. Robert Perry drowned.” In August 1970, Perry, of East St. Louis, had gone swimming in a quarry with fellow survivor Frank Bazos of Aurora. Despite desperate efforts by Bazos, Perry drowned — just a day before he was to start a new job.

“When Perry died after having gone through the fire, I realized that when it’s your time to go, it’s your time,” Beranek continued. “There’s nothing I could have done.”

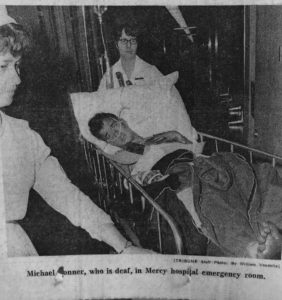

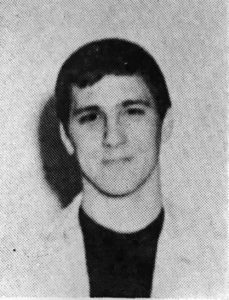

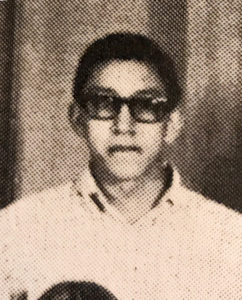

Kennedy and Zanger were the only two fatalities of the fire; the 14 injured ISD students included: Charles Bright, 17; Thomas Byrnes, 15; Michael Davis, 15; Freeman Harper, 16; Albert Jones, 18; David Newcum, 14; Scott Noyes, 14; Larry Peterson, 16; David Reynolds, 16; Danny Thomas, 18; Michael Tonner, 17; and Michael Ubowski, 14.

The cause of the fire was never confirmed; it was later revealed that there had been a fire on the same floor two years earlier.

Today

Zeke Beranek, who turns 86 in February, lives in Jacksonville, Ill., with his wife of 55 years. After 32 years, he retired from education and now works with H&R Block as a tax preparer when not walking his dogs.

Charles Bright, 65, has worked for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for 40 years, and is considering retirement. He has two children and one grandchild, and makes his home with his wife Genevieve in Schaumburg, Ill.

Freeman Harper, 64, retired from a career as an educator at the Phoenix Day School for the Deaf, and resides in Iowa City, Iowa.

David Reynolds, 63, became an educator and worked for years at the Indiana School for the Deaf before moving west to Fremont, Calif. He has three sons, and has an acting career, most notably as Dr. Wonder on Dr. Wonder’s Workshop. He and his wife, Alyce Slater Reynolds, recently relocated to Riverside, Calif., where he intends to create a movie about the Chicago fire, among other films.

David Reynolds, 63, became an educator and worked for years at the Indiana School for the Deaf before moving west to Fremont, Calif. He has three sons, and has an acting career, most notably as Dr. Wonder on Dr. Wonder’s Workshop. He and his wife, Alyce Slater Reynolds, recently relocated to Riverside, Calif., where he intends to create a movie about the Chicago fire, among other films.

Dale Saline, 62, retired from the U.S. Postal Service after 20 years. He now works at his family’s pig farm in Rio, Ill. and lives with his wife.

Click here for my thoughts on this story in ASL and English.

All photographs are taken from the Chicago Sun Times, Chicago Tribune, Chicago Daily News, the Illinois Advance, and the interviewees unless otherwise indicated. Special thanks go to Joan Engelmann and Rosa Ramirez.